Natural Born Litigators: The EDC

Big bad oil companies and their big bad, money-hungry legal teams. Sound familiar? Across the globe, corporations have tried to build countless new projects at the expense of environmental sanctuaries, oceans, wildlife, and our communities. Key word: tried.

So who is saving us from environmental destruction?

Who is the voice of our people and takes action against these scheming conglomerates?

Would you believe me if I told you it is a small nonprofit, public interest firm in Santa Barbara, California? These people are the environmental superheroes, and they call themselves the Environmental Defense Center. But who exactly are these people, and where did they come from?

On January 28, 1969, a catastrophe struck off the Central Coast of California: Union Oil’s Platform A, located in the Dos Cuadras Offshore Oil Field, had a major well blowout, putting Santa Barbara County on the map for environmental awareness. Not only did the spill make headlines across the globe, it also became a catalyst for the creation of Earth Day, numerous environmental studies programs in universities across the country, and helped establish federal and state environmental protection laws and agencies.

The first environmental law passed after the spill was the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires all agencies to consider what the environmental impacts may be before embarking on or approving a project. Additional acts passed include the Clean Air Act, Endangered Species Act, and Coastal Protection laws.

Despite all the bad, something good had emerged — the Environmental Defense Center (EDC), a mighty 501(c)(3) nonprofit of eleven staff members that works with other local nonprofit organizations to advocate for environmental protection and provide legal counsel. The EDC is one of a kind, serving as the only public interest environmental law firm between Los Angeles and San Francisco focusing on climate and energy, environmental justice, and protecting land, water, and the ocean.

But how did EDC come about amidst all of the chaos?

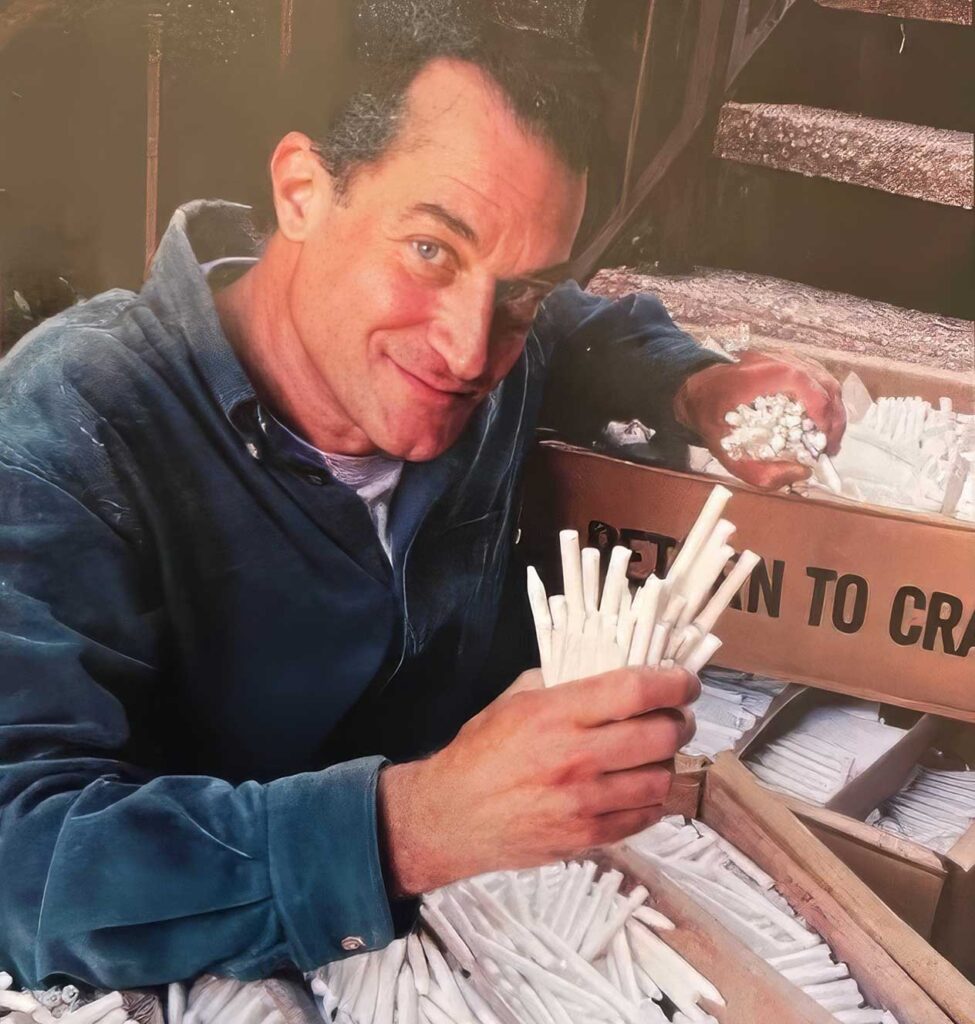

“Marc McGinnes, who helped found the Environmental Studies Program at the University of California Santa Barbara, was an attorney who tried to get his law firm to take environmental cases, but they said they weren’t interested,” recalls EDC’s (environment-protecting, badass lawyer version of Tony Stark), Linda Krop.

So McGinnes tried to get other attorneys to take cases, but they didn’t have the time and expertise. He then approached a group that had actually formed as a result of the oil spill called Santa Barbara Citizens for Environmental Defense.

“They were the advocacy group that came out of the oil spill. He knew that they were interested in advocating before different agencies and trying to get good decisions made and avoid bad decisions, so he approached them and said, ‘Hey, how about if we add lawyers to your group?’ They loved that idea, so they launched the Environmental Defense Center in 1977. He was the first chief counsel.”

The objective of EDC was — and still is — to bridge the gap between a galvanized community that wants to avoid another ecological disaster and the newly created environmental protection laws.

Not only does EDC serve as a protector of environmental and public safety, but it also serves as a tool of mobilization and legal support for organizations and communities that want to take action to protect the environment. EDC was formed not to serve as an independent organization, but to be the legal backbone for other groups.

For almost 50 years, EDC has represented 140 organizations, ranging from local groups such as Save Ellwood Shores to national groups like the Sierra Club and the Surfrider Foundation. Its nonprofit status makes EDC unique from other public interest law firms that charge their clients fees.

Although some clients provide financial support, EDC mainly relies on donations, fundraising events, foundation grants, and attorney fees from successful cases to help as many causes as they can without taking any governmental money.

Since it is the only firm of its kind in the region, EDC receives a plethora of requests. Though it is small and mighty, EDC cannot take on every case presented to it and instead makes referrals to other firms. The staff decides what cases they will represent through an extensive selection process and criteria established with EDC’s Board of Directors.

With the Board, they decide if the issue is significant to the environment and community, involves environmental justice threats, and aligns with EDC’s mission and priorities — mainly concerning public health or the environment.

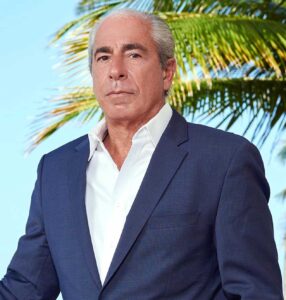

“I like to say that the Environmental Defense Center is a law firm and an environmental organization because we do everything from litigation to education and everything in between,” says Krop.

When she attended UC Santa Barbara for her undergraduate studies, Linda became a volunteer for EDC, working on the two biggest environmental issues on campus at the time: the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant — which she continues to be involved with at EDC (full circle, superhero moment) — and fighting a liquefied natural gas project off Point Conception.

Linda expresses her gratitude for Marc McGinnes when she states, “I was very fortunate to have Marc McGinnes as my mentor. When I graduated from UCSB and wanted a career in environmental advocacy, people suggested that I talk with him, and he was the one who recommended that I go to law school — that had not been on my radar at all — but he said, ‘Well, why don’t you go to law school and you could intern or clerk with the Environmental Defense Center. We need more public interest lawyers.’”

Think of Marc as the Iron Man to Krop’s Spider-Man (Tom Holland’s version).

“I call myself an accidental lawyer, and I had a very unusual path. I grew up in a family that was very active in social issues and political campaigns. My mother helped found the local chapter of the League of Women Voters, and she would take me to forums and meetings. She would take me precinct walking, and she was very focused on social and environmental issues and civil rights. So I had that activism background. I also had a love of nature,” Linda shares when referring to why she wanted to become an environmental lawyer.

After receiving her JD and clerking for EDC for three years, Linda became an official staff attorney in 1989 and the chief counsel in 1999.

“I ended up being really happy to have a career in law. I feel like it’s the most effective way to be an advocate. Just being able to actually impact the decision-making and make a difference in that way — it’s the most active you can get in creating change.”

During her 35 years at EDC, Linda has created long-lasting environmental changes, such as terminating 40 federal oil and gas leases offshore California in 2005, defeating several oil drilling projects, and contributing to the preservation of areas for public access and ecological protection.

Not only does she save the environment with her superhero staff, but she also teaches students at UC Santa Barbara how to make an impact through environmental law.

When talking about environmental advocacy and preserving land from environmentally harmful developments, it is crucial to acknowledge those Indigenous to the land that EDC works so vigorously to protect — the Chumash people.

EDC recognizes that its office sits on unceded, occupied, stolen lands on Shmuwich (Chumash) Territory and is committed to making space to elevate Indigenous voices and support local Chumash and Indigenous communities in their work to protect the environment.

In fact, two of EDC’s very first cases represented the Chumash. One project involved fighting the liquefied natural gas project off Point Conception, a sacred Chumash site. Point Conception is considered the Western gate for the Chumash; when mortals pass away, that’s where their souls leave the Earth and transition from this world to the next.

Additionally, EDC represented the Chumash in a case to protect Hammond’s Meadow, where a proposal for a large development would have not only destroyed habitat but also blocked public access to the beach. These are two projects EDC successfully won and shut down before causing further damage.

Linda highlights EDC’s long-standing connection with the Chumash, having represented various Chumash bands throughout its existence — whether federally recognized or not.

“We have been working very closely with the Northern Chumash Tribal Council in San Luis Obispo to support the designation of a new national marine sanctuary that will probably be designated by the end of 2024. It’s the first tribally nominated sanctuary in the country’s history. We are also partnering with the Santa Ynez Band, which is the only federally recognized tribe, on creating a petition to establish a marine protected area off Carpinteria, CA.”

It often seems like Big Law firms are the ones who handle cases against massive oil conglomerates. Money and time are of the essence when facing these black-hole, bottomless-pit companies with endless supplies of cash and lawyers.

You would think a nonprofit firm as small as EDC would be positioning itself between a rock and a hard place, but in its 47 years of existence, EDC has learned how to stand its ground.

EDC has gone against powerful companies from ExxonMobil to BHP Billiton. In 2015, a pipeline spill shut down several offshore oil platforms owned by ExxonMobil in the Santa Barbara Channel — four of them permanently due to pipeline corrosion.

As a result, Exxon applied for county approval to load its oil onto trucks and transport it up the Gaviota Coast and across Route 166 — a very dangerous highway leading to Bakersfield, California. Exxon proposed sending 70 loads daily, equating to 140 truck trips per day.

The county planning staff began recommending approval by preparing an environmental impact report (EIR) that minimized the risk of spillage, claiming there was only a chance of an oil tanker truck spill on Highway 101 every 52 years and on Route 166 every 17 years.

While waiting for the application to be considered, a major oil tanker truck accident occurred on Route 166, spilling oil into the Cuyama River. This is when EDC swooped in.

According to Linda, EDC doubted the proposed EIR and hired three undergraduate interns from UC Santa Barbara to conduct research via Public Records Act requests to agencies such as sheriffs, highway patrol, oil spill response units, and through media research.

The interns developed a report showing that in the last 15 years, there had been eight oil tanker truck accidents along the proposed route — six in the last six years — resulting in deaths, fires, explosions, oil spills, and road closures.

“We submitted our report, which was very different from what the EIR said,” Linda explains. “We convinced the supervisors to deny the application, even though staff had recommended approval.”

Additionally, EDC prevented the county from allowing ExxonMobil to restart three oil rigs. Boom. Goodbye. Vetoed.

ExxonMobil then sued the county.

EDC intervened on behalf of its clients — local, state, and national groups — and defeated ExxonMobil in court with back-to-back wins.

“The judge actually cited the Environmental Defense Center’s evidence,” Linda reveals.

EDC has defeated ExxonMobil, Mobil before the merger, and Chevron — repeatedly.

The fight didn’t stop there.

In 2007, BHP Group Limited (formerly BHP Billiton) proposed a liquefied natural gas project off the coast of Oxnard, California.

“They picked Oxnard because they thought it was a disadvantaged community — low-income, predominantly Hispanic — and they picked Oxnard. Well, that’s in our backyard,” Krop says.

Despite support from Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and President George W. Bush, EDC took the case.

“We defeated them. We killed the project.”

DAVID VS. GOLIATH

As a small firm battling powerful corporations and political figures, EDC has faced obstacles — but the laws remain strong.

“What can sometimes be challenging are the politics,” Linda notes.

In 1998, the Hearst Corporation proposed four major resorts between Cambria and San Simeon, doubling the size of both towns.

Despite initial county approval, EDC proved Hearst violated the California Coastal Act and successfully reversed votes at the Coastal Commission.

FRACKING BEGONE

EDC uncovered offshore fracking permits through Freedom of Information Act requests after agencies denied fracking activity.

They sued under NEPA and the Endangered Species Act — and won.

“All fifty-one fracking permits are now expired.”

As it approaches 50 years of public service, the Environmental Defense Center continues its work through four core programs: Climate & Energy, Environmental Justice, Land and Water, and Ocean Protection.

We thank Linda Krop, the staff, and the Board of Directors of the Environmental Defense Center for their unwavering commitment to protecting our environment.

Featured Articles

Meet our Contributors

Discover Next

Insights from Experts

Learn from industry experts about key cases, the business of law, and more insights that shape the future of trial law.